They say practice makes perfect, and every city, country, or empire wants their fighters to be the best, the strongest, and the most elite. The staple of any great nation would be the military that protects it. Any good military needs athletes that train every day, from cardio to weightlifting, and the Pell was a great tool for practice since it provided both. A Pell, which was a straight pillar of wood, the height of a man and 6 to 12 inches thick, was made to be hit. Stewart Feil points out in his article, “Essential Training: the Pell”, that the Pell is used to learn proper striking technique, including power, energy focus, accuracy, and range. From Roman Legions to modern Marshal Artists, it has proved to be a reliable way to practice form and stamina.

The earliest mention of the Pell was in the first century C.E, by the Roman writer Juvenal. He recalled the training of gladiators, asking “Who has not seen the dummies of wood they slash at and batter whether with swords or with spears, going through all the maneuvers?” (Juvenal, “The Female Gladiator”). Gladiators reportedly fought against dummies made of hay and straw (Grant, p. 34 & 40). The purpose of these drills was not to make them stronger, but to work on muscle memory and technique. As you swing the sword in the same motion, to the same spot, with the same amount of force, you begin to do it easier.

Another notable Roman is General Flavius Vegetius Renatus, who would write down his thoughts and strategies. He complained that people did not know how to professionally train an army, and that Rome needs to go back to the earlier days when they had strict workout regimens (Clements, “On the Pell”). He required his soldiers to do about half an hour twice a day. Vegetius thought that a well-trained army was better than employing mercenaries, which was what Rome was using at the time. Vegetius had his writings published and it influenced many medieval generals.

Vegetius wanted to train his men like gladiators, and so he had a routine just like a gladiator’s. He instructed them to put a 6-foot post in the ground until it did not wobble when struck. He then told them to fight it like a real enemy. They should try different ways of striking, from the head to the body to the legs. By doing this, the soldier used every part of his body, giving a full body workout.

There were multiple different strength training that Vegetius would use the Pell for. One exercise would use wicker shields and wooden swords that were twice the weight of normal ones, and the soldiers would have to get used to the drastically overweight gear (Clements, ““Get Thee a Waster!”). He referred to this exercise in his writings, stating that “This is an invention of the greatest use, not only to soldiers, but also to gladiators. No man of either profession ever distinguished himself in the circus or field of battle, who was not perfect in this kind of exercise.” (qtd. in Clements, “On the Pell”). It should be noted that Vegetius was only able to use part of this training while on the battle field, as the Romans mainly fought in tight formation with not much room for cutting, but the next time period would find these Pell tactics more useful.

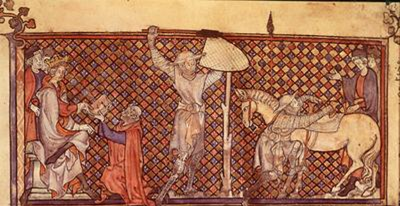

The medieval age was a time associated with knights of shining armor and glistening swords, heavy charges of horse and mail, and a great setting for your next D&D campaign. While all of these are true, people often neglect how actual medieval combat was conducted. For most of the period, armies were not made up completely of well-trained full-time fighters, but rather they were a group of farmers, crafts men, and peasants that would be given weapons and told to go assist the main (usually more trained and reliable) vanguard. These troops had an extremely limited amount of training, so the training they did get had to be both effective and efficient. The Pell reemerged as the main training focus, and Vegetius’s writings became the manual for many great Generals, to include George Washington.

In 1489, a writer by the name of William Caxton translated the writings of Vegetius to English, from a French translation of Latin. This book tells modern historians about the practices done both in Vegetius’s time, and what the people in Caxton’s time did as well. People of the time would “take axes and swords and all manner of other weapons of war and assault and force themselves to smite against certain stakes” (qtd. in Clements, “On the Pell”). Caxton also adds that they would change up the purpose of the exercises depending on what needed work. He said they would strike quickly and sporadically to work on speed, and slowly but precisely to work on strength. By moving quickly, they focus on making their bodies move, and can push their endurance for how long they can go at it. This build both muscle memory and reinforces actual combat. Moving slowly is harder since you cannot use the momentum of the sword, so it forces soldiers to be strong and be precise. This also engraves muscle memory since it becomes easier to remember when you go slowly.

You know how we all sometimes sing our ABCs every once and a while to remind ourselves what order those letters are in? Or how a group of kindergarteners will sing “the clean up song” to remind them what they should do at the end of the day? Turns out, there was a sing song about the Pell. The Poem of the Pell was written sometime around the 16th century and is quite interesting (see Appendix A). The poem tells us that anyone who does not practice with a Pell is just plain bad at fighting. It reinforces the necessity for double weighted weapons, and say’s that fighting is a discipline. The poem makes it more than clear that swordsman ship is an art and is not just swinging around a sword and being strong. Another value that the poem made noticeably clear was that the posture and stance. It reinforced that (just like almost every sport) the way you plant your feet and how you position your body.

Today, you do not see nearly as many fighters using the Pell for everyday practice, but it does have a spiritual successor. Walk into almost any gym and you will probably find at least one punching bag. Many people, even if they barley do any boxing, use the punching bag to let off steam. Punching bags can increase endurance, making many athletes use it to blow off steam. The same principles are present with a punching bag like the Pell, it’s supposed to make you do a task better, for longer, so you won’t get yourself hurt if/when the time comes to use those skills.

Both punching bags and the Pell are excellent ways to improve yourself. From Gladiators, to Knights, the Pell was a valuable training tool. With some of the most impressive armies of their time using it for training, it has some unbelievably valuable endorsements. The Pell is not only a great device for training, but it makes a good workout. Being able to work on different parts of fitness using just a wood post is amazing and easy. I recommend that everyone try some Pell practice occasionally. I use the Pell as part of my physical fitness training.

Bibliography

Clements, John. “Get Thee a Waster!” Association for Renaissance Martial Arts, www.thearma.org/essays/wasters.htm#.XzWmDaeSlPb.

Celements, John. “On the Pell.” Association for Renaissance Martial Arts, www.thearma.org/essays/pell/pellhistory.htm#.XyxNyIEiehA.

Feil, Stewart. “Essential Training: The Pell.” Association for Renaissance Martial Arts, www.thearma.org/essays/pells.htm.

Grant, Michael. Gladiators. Barnes and Noble, 1967.

Juvenal. “The Female Gladiators.” Satires of Juvenal, www.tribunesandtriumphs.org/roman-life/satires-of-juvenal.htm.

Strutt, Joseph, and J. Charles Cox. Methuen, 1903, The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, archive.org/details/sportspastimesof00struuoft.

“Vegetius.” Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/biography/Vegetius. “William Caxton.” Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/biography/William-Caxton.

Appendix A

THE POEM OF THE PEL

Translation based on the Cambridge Version (1458-1460)

(https://aranmore.wordpress.com/2015/04/22/the-poem-of-the-pel/)

The discipline and exercise of the fight

was this: To have a pel or pile upright

Of a man’s height, thus the old and wise do write

With this a bachelor, or a young knight

Shall first be taught to stand, and learn to fight

And with a fan of double weight he takes as his shield

And a double-weight mace of wood to wield.

This fan and mace, either of which are of double weight

Of shield, swayed in conflict or battle,

Shall exercise swordsmen, as well as knights,

And no man, as they say, will be seen to prevail,

In the field, or in castle, though he assail,

Without the pel, being his first great exercise,

Thus write warriors old and wise.

Have each his pel or pile up-fixed fast

And, as it were, upon his mortal foe:

With mightiness the weapon must be cast

To fight strong, that none may escape

On him with shield, and sword advised so,

That you be close, and press your foe to strike

Lest your own death you bring about.

Impeach his head, his face, have at his gorge

Bear at the breast, or spurn him on the side,

With knightly might press on as Saint George

Leap to your foe; observe if he dare abide;

Will he not flee? Wound him; make wounds wide

Hew off his hand, his leg, his thighs, his arms,

It is the Turk! Though he is slain, there is no harm.

And to thrust is better than to strike;

The striker is deluded many ways,

The sword may not through steel and bones bite,

The entrails are covered in steel and bones,

But with a thrust, anon your foe is forlorn;

Two inches pierced harm more

Than cut of edge, though it wounds sore.

In the cut, the right arm is open,

As well as the side; in the thrust, covered

Is side and arm, and though you be supposed

Ready to fight, the thrust is at his heart

Or elsewhere, a thrust is ever smart;

Thus it is better to thrust than to carve;

Though in time and space, either is to be observed.

This is a well written paper. Until now I took the pell for granted and though it was an artifact solely of the SCA. I learned a lot from reading this.

Thank you for sharing!

Very well done! Good writing and references, and of course, pictures. I look forward to seeing more.

Great paper! Well thought out, well cited, and you make an excellent point.

This is very good work. Your research is interesting and informative, and I really liked the inclusion of the poem! I hope you will continue to produce papers like this, and continue your research into many more subjects.